Electronic reference

|

Abstract

|

Table of contents

|

Full text

|

Notes

|

Keywords

|

Author(s)

|

Bibliography

|

Electronic reference

|

Abstract

|

Table of contents

|

Full text

|

Notes

|

Keywords

|

Author(s)

|

Bibliography

|

Electronic reference

Improvisation, Interaction and Intermusicality in the Bill Evans Trio

Improvisation, interaction et intermusicalité dans le trio de Bill Evans

Michael P. Mackey

Abstract

Traditional jazz pedagogical and analytical practices typically favor transcription and analysis of characteristic solo improvisations as a means to ascertain the conceptualizations of master musicians. However, these practices most often neglect the improvised processes of interaction that reciprocally inform and inspire solo, accompaniment, and other gestural interactions that occur in performance. Drawing from Ingrid Monson’s Theory of Intermusicality, I aim to ascertain the communicative dialogue coded in the melodic, harmonic, and/or rhythmic content produced by the interaction and interplay in the collaborative improvisation of the Bill Evans Trio: pianist Bill Evans, bassist Scott LaFaro, and drummer Paul Motian. I present excerpts of my personal trio transcriptions of Cole Porter’s “All of You,” as recorded live in 1961 for the trio’s Village Vanguard Sessions, for intermusical analysis. In doing so, I consider how this particular trio challenged conventional practices by utilizing improvisation as a vehicle for interaction and interplay in jazz performance. By utilizing the Bill Evans Trio as a case study, I hope to entice further considerations of intermusicality in jazz scholarship, pedagogy, and performance, so to better engage the musical, social, and cultural dialogue central to the jazz tradition.

Les méthodes traditionnelles d’analyse et de pédagogie du jazz favorisent de manière générale la transcription et l’analyse de solos improvisés caractéristiques, afin de déterminer les processus de conceptualisation des grands musiciens. Cependant, ces méthodes négligent pour la plupart les processus d’interaction improvisés qui façonnent, et réciproquement inspirent, les solos, l’accompagnement et les diverses interactions gestuelles qui se présentent au cours d’une performance. En prenant pour support la théorie de l’intermusicalité d’Ingrid Monson, je souhaite montrer que le dialogue communicatif est encodé dans le contenu mélodique, harmonique et/ou rythmique produit par l’interaction dans une improvisation collaborative du trio de Bill Evans avec le bassiste Scott LaFaro et le batteur Paul Motian. Pour cette analyse intermusicale j’utilise des extraits de transcriptions personnelles du morceau « All of You » de Cole Porter, tel qu’il a été enregistré en 1961 en public au Village Vanguard. Ce faisant, j’étudie en quoi ce trio tout particulièrement a remis en cause les pratiques conventionnelles en utilisant l’improvisation comme vecteur pour l’interaction dans les performances de jazz. En utilisant le trio de Bill Evans comme sujet d’étude, j’espère susciter davantage de considération pour l’intermusicalité dans les études, la pédagogie et les performances de jazz, de manière à engager un dialogue musical, social et culturel, central pour la tradition du jazz.

Full text

In jazz research and performance practices, emphasis has long been awarded to musicians who exhibit virtuosity of solo improvisation. Whether Louis Armstrong’s assertive cadenza on “West End Blues” or John Coltrane’s blazing acrobatics on “Giant Steps,” select recordings such as these have come to represent the genius of iconic individuals. As a result, generations of scholars, performers, and pedagogues have turned to transcribing improvised solos to gain insight into the improvisatory techniques of the masters. In most cases, however, the practice of solo transcription inadvertently disengages the improvised processes of interaction that occur between musicians during performance. Furthermore, transcription transforms an active performance into an inactive musical product – a text – thereby neglecting the processes of artistic creation that simultaneously inform and have been informed by musical and social interactions with others. In jazz improvisation, all of the players are compositional participants, in which spontaneous decisions are made regarding what to play and when to play it within the framework of the groove [1]. As such, the indeterminacy of collaborative improvisation structurally resembles conversation much more so than text, thus necessitating a revision of analytical practices.

With emphasis on the communicative properties of collectively improvised performance, this essay explores personal and instrumental relations within the context of the jazz piano trio. This particular format can be particularly challenging for both performance and analysis because it is not simply a rhythm section minus a soloist: concepts and techniques applicable to one do not readily translate to the other. From 1959 to 1961 pianist Bill Evans’ trio with bassist Scott LaFaro and drummer Paul Motian redefined notions of the jazz piano trio format, reaching beyond traditional conceptions of time, form, instrumental roles, improvisation, and interplay. The group championed ensemble cohesiveness and collaboration over solo-centered displays of virtuosity. Though commonly referenced under the name of its leader, the members of the Bill Evans Trio functioned as three equal constituents and the uniqueness of this particular collaboration must not go unnoticed. Applying Ingrid Monson’s theory of intermusicality to the processes of interplay and improvisation in the jazz piano trio format reveals that each distinctive combination of interacting personalities produces distinct, idiosyncratic intermusical revelations. Along with Monson, Paul Rinzler and Paul Berliner have also suggested that discussing the musical processes observed in performance with the performers themselves direct us to specific points of interaction, while simultaneously honoring the human spirit of music-making when analyzing transcriptions. Since the subjects of this analysis are no longer living, we must seek alternate means to gain insightful access into the improvised processes of interplay and interaction. To best meet the challenges of analyzing piano trio improvisations with attention to both musical and social considerations, I begin by examining several influential texts on the subject of improvised interactions in jazz from which I will construct new perspectives on the matter for the purposes of this paper.

Writings on Jazz Interaction

Scholarship on the interactive properties of jazz improvisation has been rather scant, save the influential work of three scholars: Paul Rinzler, Paul Berliner, and Ingrid Monson. Paul Rinzler’s 1988 article “Preliminary Thoughts on Analyzing Musical Interaction Among Jazz Performers” was among the first to address the issue. Dismayed by trends at the time that favored computational and scientific models for musical analysis, Rinzler feared that such analytics neglected the most crucial human process in jazz performance – musician interaction [2]. In response, he delineates the “rules of the game” or the presupposed functions of each instrument in the ensemble and how jazz musicians negotiate these individual roles with varying degrees of creativity and aesthetic sensibility while satisfying more general positions as accompanist or soloist. Performers are then analyzed according to measurable amounts of creativity and interaction as present in a group performances in relation to the game rules, including call and response, fills, accentuation of phrase and large form structures, common motives, and rhythm sections responses to the “peaks” of the soloist [3].

Like Rinzler, much of the musical analysis in Paul Berliner’s monumental Thinking in Jazz: The Infinite Art of Improvisation [4] is framed in relation to the constant negotiation between adherence to and radical departures from stylistic conventions. However, Berliner extends his analytical considerations by utilizing ethnographic practices to specifically examine musicians’ decision-making processes in improvised performance, as they constantly shift between complementary positions for the sake of group unity and musical cohesiveness [5]. His extensive interviews with prominent jazz musicians also reveal deeper understandings of how stylistic conventions associated with particular jazz idioms not only guide solo and accompaniment considerations but also shape musicians’ expectations for group interplay. He elucidates that the players must maintain constant balance between developing individual ideas for musical invention and anticipating and/or interpreting another’s ideas for the sake of continuity. Unexpected departures by a singular participant require the others to react at an instant by maneuvering or responding [6].

Berliner’s discussions with the musicians themselves are particularly informative. Most notable perhaps is the oft-cited metaphor of group improvisation as conversations between players in the jazz language [7]. Citing the rhythm section’s ongoing improvised accompaniment within the groove as most representative of this metaphor, he posits that the extent of interplay is ultimately dependent upon each improviser’s aural skills and ability to instantly grasp and respond to one another’s ideas. Here Berliner considers how a musician’s capacity to do this reflects years of training that began with efforts to acquire a “jazz vocabulary” through exercises in transcription and recreation with individual difference [8]. His attentiveness to processes of musical learning and improvisational skill development directs our analysis towards individualized narratives of study, conceptualization, and performance.

In Saying Something: Jazz Improvisation and Interaction [9], Ingrid Monson offers her own “interpretive trajectory with ethnographic materials” about the rhythm section and improvisation, guided by instrument roles, responsibilities, musical options, and social frameworks. Like Berliner, Monson contests that “interacting musical roles are simultaneously interacting personalities, whose particular characters have considerable importance in determining the spontaneity and success of the musical event [10]”. However, at a deeper level, her argument is extended to consider how social, cultural, and racial constructs are exhibited through interactive jazz improvisation. She asserts that a close reading of interactive improvisation reveals much about this constant intersection of sound, structure, and social meaning and can inspire “a more cultural music theory and a more musical cultural theory [11]”. Monson, like Berliner, privileges the documentation and interpretation of vernacular perspectives, as offered by the musicians themselves, and considers it to be the only ethical point of departure for work in jazz studies and ethnomusicology. As such, “Saying Something concentrates on what implications musician’s observations about musical processes may have to the rethinking of musical analysis and cultural interpretation from an interactive point of view, with particular attention to the problems of race and culture [12]”.

Theorizing Improvised Interaction

The Groove

Rinzler, Berliner, and Monson all begin their discussions with what they consider to be primary and fundamental to group interaction – the groove. It is the one element perhaps most obvious to veteran jazz musicians and is yet the most elusive to analysis. This negotiation of a shared sense of the beat incorporates connotations of stability, intensity, and swing. Though the groove unites all improvisational roles into a musical whole, it often correlates to the effective coordination of the rhythm section as a singular unit. Striking a groove also implies a sense of rhythmic phrasing, both within and outside the pulse; the stronger the groove or the time feel, the easier it is for soloists to take risks with rhythmic phrasing. With experience, players develop the ability to negotiate even more subtle nuances involving the collective maintenance of the beat: variations, fluctuations, and interpretations of the beat (e.g. playing “before,” “on top of,” or “after” the beat).

Defining and maintaining the beat is an ongoing responsibility for all members of the ensemble – even while attending to the complementary interactions between participants – to ensure a truly collective performance. Whether implicitly stating the time or subtly implying it, the time-keeping responsibility is often rotated between players, resulting in a juxtaposition of time or polytime within the overarching groove. Though, as Berliner points out, the trade-off is simple: the freedom of one restricts another [13]. The implications of a player having good time or a rhythm section striking a groove are so essential that Monson discovered in her interviews that jazz musicians often emphasize time and ensemble responsiveness as indicative of higher levels of improvisational achievement, whereas harmonic and melodic competence are inferred skills [14].

Improvisation as Conversation

In noting that communities of musicians often function as learning environments for young, aspiring players, Berliner concludes that collaboration and communication are embedded into the social and musical fabric of jazz improvisation. According to Monson, this points to a possible reason why musicians rely on the metaphor of conversation to describe the improvisational process: jazz as a musical language, improvisation as musical conversation, or when a musician plays a particularly good improvised solo, they are “saying something”. Since this metaphor is so strong among jazz musicians, Monson asserts that “meaningful theorizing about jazz improvisation at the level of the ensemble must take the interactive, collaborative context of musical invention as a point of departure [15]”.

Intermusicality

Though the conversation metaphor used by jazz musicians elicits innate structural connections between music, speech, and the sociability of jazz performance, Monson suggests that this metaphor also includes a temporal dimension. She posits that analyzing the interaction between improvising musicians in performance reveals that musical sounds can refer to the past and offer social commentary through irony or parody. In doing so, Monson frames musical functions as relational and discursive, rather than simply rooted in sound. In other words, when a jazz musician demonstrates an awareness of musical history through quotation, imitation, or evocation, the sonic material of his/her performance contains allusions to dimensions beyond melody, harmony, and rhythm alone. Whether subtle or overt, these audible references simultaneously influence how a collaborating musician or audience member interprets and/or reacts to any singular moment or combination of sonic elements in the present performance. Through what she calls intermusicality, musicians convey both cross-cultural and intra-cultural ironies by manipulating previous forms, whether in transforming American popular song, referencing European classical repertoire, inserting humor, or quoting other musicians and styles within or outside the jazz tradition [16].

As part of a longstanding tradition within African American musical practices, the transformation of such a piece into an alternative musical aesthetic offers the potential for ironic interpretations of musical devices and cultural meanings. When a jazz musician alters a previously composed work by modifying its form, instrumentation, orchestration, and other stylistic devices, it is not intended to replace the original version, but rather extend and trope figures present in it. Monson reminds us, however, that an ironic interpretation at either the musical or cultural levels will always be subject to the eye (or in this case the ear) of the beholder. Whether a participating musician or an audience member, each individual’s ability to recognize and interpret intermusical cues in a performance and the extent of such recognitions is subject to such factors as age, experience, aural skills, and familiarity with musical and cultural aesthetics. One’s reaction to and evaluation of intertextual influences, references, and (dis)connections will also reflect the strength of his/her personal and cultural identities in relation to music and beliefs and/or boundaries (if any) regarding musical style and aesthetic. Further complicating the issue, jazz musicians often incorporate elements from a range of musical and cultural expressions, both within and outside the tradition, into the sonic detail of their performances and compositions [17].

Due to the absence of words in instrumental jazz improvisation, Monson suggests that the notion of intermusicality offers a way to consider relationships in communicative processes that occur primarily through musical sound. For instance, the intermusical aspect of musical perception helps to explain the ability of musicians to pick up on one another’s ideas and to find chemistry in their musical offerings. But Monson explains that intermusicality is not limited to theoretical constructs alone; “The idea that intermusical associations are part of the musical communication process during performance highlights the practical […] implications of the ideas of intermusicality” because the intimate, social process of developing musical ideas in improvised performance necessitates interactive musical responsiveness among all participants to referential or familiar musical gestures, whether rhythmic, melodic, harmonic, and/or textural [18].

Framing Analysis

Privileging the authoritative voice of the artists themselves as integral to the analytical framework, Monson contests that while recording transcriptions offer a visual representation of the musical conversation between musicians “in time,” the added element of the musician’s post-performance commentary directs us to the conversation “over time” and its intermusical ramifications. In her own work, Monson discusses her observations of a Jaki Byard Quartet performance through the group’s leader and discovers new connections that she believes could have only been made through her conversations with him. But in the event that we cannot gain physical access to the musicians, as is the case with the subjects of this paper, we risk analyzing their musical contributions, whether compositions, performances, recordings, improvisations, or otherwise, as byproducts of musical activity rather than as musical activity itself, thereby privileging the absolute over the discursive. Reading transcribed interviews as texts alone bear the same risk for analysis.

In absence of the original participants of this study, insights are gained by examining archived interviews in which the musicians disclosed key information about both individual and group conceptualizations. Representative recorded evidence follows for transcription and analysis. On-site or “live” recordings offer unadulterated representations of performances for procedural analysis of improvisation and interaction. Riverside’s The Complete Village Vanguard Recordings of the Bill Evans Trio has proven to be of particular value to this study. All tracks were recorded live and the inclusion of previously unreleased tracks offer the opportunity to compare multiple versions of the same tune, which in this case was recorded three times on the same day.

The Forming of a Trio

When his new trio was formed, Evans had said that he hoped it would “grow in the direction of simultaneous improvisation rather than just one guy blowing followed by another guy blowing,” elaborating:

If the bass player, for example, hears an idea that he wants to answer, why should he just keep playing a 4/4 background? The men I’ll work with have learned how to do the regular kind of playing, and so I think we now have the license to change it. After all, in a classical composition, you don’t hear a part remain stagnant until it becomes a solo. There are transitional development passages – a voice begins to be heard more and more and finally breaks into prominence […] Especially, I want my work – and the trio’s if possible – to sing. I want to play what I like to hear. I’m not going to be strange or new just to be strange or new. If what I do grows that way naturally, that’ll be O.K. But it must have that wonderful feeling of singing [19].

On meeting Scott LaFaro at an audition for Chet Baker in the late 1950s, Evans’s first impression was that “he was a marvelous bass player and talent, but it was bubbling out of him almost like a gusher. Ideas were rolling out on top of each other; he could barely handle it. It was like a bucking horse [20]”. To Evans’ producer Orrin Keepnews, it seemed as though the relationship between Evans and LaFaro had great significance on the pianist’s ensemble conceptions. Keepnews writes, “It is difficult to determine when the concept of treating the trio as three almost-equal voices entered the picture. In retrospect, Bill talked on later occasions of having had the idea for some time, but there is good reason to believe that it really entered the picture as part of Bill’s initial reactions to working with Scott [21]”. The same could certainly be true of Evans’ relationship with Motian as well. Determined to create a particular unified aesthetic, he initially questioned using a drummer in the first place:

I think in terms of a number having a total shape. For example, I try to avoid getting to full intensity too early. Any one thing done for too long gets tiring. Contrast is important to me. I even thought that drums would be a problem and we might be better without them. It was remarkable that Paul Motian came along and identified with the concept so completely [22].

Evans later indicated how pleased he was to find two musicians who were not only compatible, but also willing to dedicate themselves to the musical goal of becoming a trio. In fact, the three made an agreement to decline any other work that would come up for the sake of the group. In an interview, Motian recounted a month-long engagement at the Showplace in Greenwich Village, one of their first booking together:

I felt that was actually the real beginning. Magic. Everything fit. The music was beautiful. We were “one voice”[…] the customary piano trio with rhythm accompaniment was a thing of the past. Not for us. We were on to something new. Something different and it felt great [23].

This quote is particularly telling in regards to the formation and early stages of development of the Evans/LaFaro/Motian collaboration – the collective conceptualization of the trio evolved from notions of vocality: the trio as “one (unified) voice,” as “three equal-voices,” “to sing,” to have “that wonderful feeling of singing,” to have “ideas rolling out…like a gusher.” More than just a metaphor for conversation-like collective improvisations, the vocal characteristics of this trio are reinforced in the intermusical analysis of the trio’s performances at the Village Vanguard.

“All of You”

Conceptualization

Over the course of five sets at the Village Vanguard on July 25, 1961, the trio recorded three takes of Cole Porter’s “All of You”, from the 1955 Broadway musical and 1957 film adaptation Silk Stockings. Only the second take was released later that year on the album Sunday at the Village Vanguard (Riverside 1961). As part of the American popular songbook, this standard presents a tremendous opportunity to discuss the ironic reversal and transformation of the original song form and the signal difference it produces as a result of this particular trio’s idiosyncratic conceptualizations of time, form, rhythm, harmony, and interplay. Because analysis of a singular recording is insufficient for ascertaining the underlying processes, concepts, and techniques, I compare constructs of all three takes from the Vanguard recordings and consider Evans’ discussion and demonstration using the same tune at the request of Piano Jazz host Marian McPartland in 1979.

It is highly unlikely that any of these musicians sourced “All of You” from a fake book or sheet music, so we begin by turning to the original rendition that would have been the basis by which most jazz musicians at the time would have constructed their own versions. A brief analysis of the original 32-bar ABAC form as transcribed from the original Silk Stockings Broadway cast recording illustrates two characteristic traits:

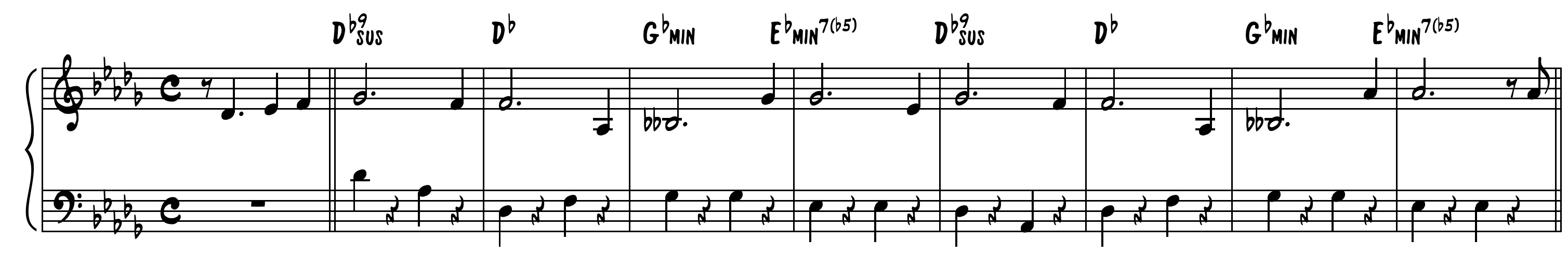

The first and fifth measure of each A-Section is a suspended tonic chord, which resolves in the second and sixth measures respectively (Fig. 1)

- Fig. 1: “It’s a Chemical Reaction, That’s All/All of You” – Silk Stockings Original Broadway Cast Recording (1989 Remastered) – 1:55

In the B-Section, consecutive harmonic inversions created by the descending bass line modify the perceived quality of the passing chord structure (Fig. 2)

- Fig. 2: “It’s a Chemical Reaction, That’s All/All of You” – Silk Stockings Original Broadway Cast Recording (1989 Remastered) – 2:09

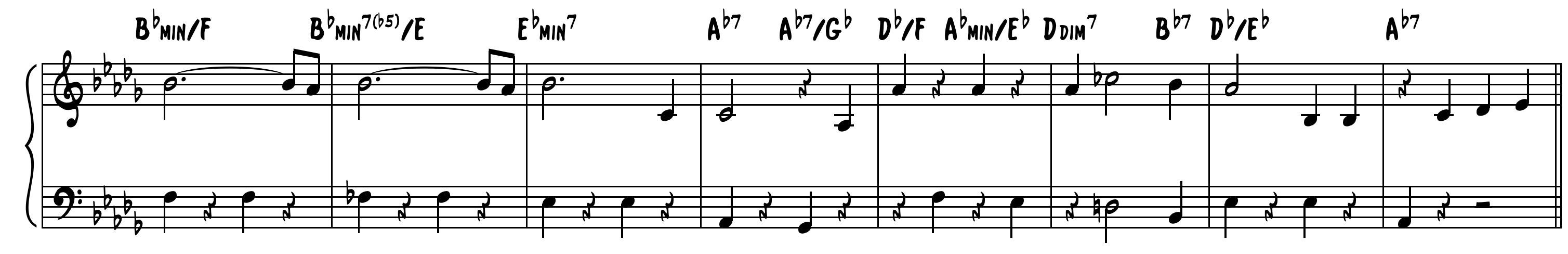

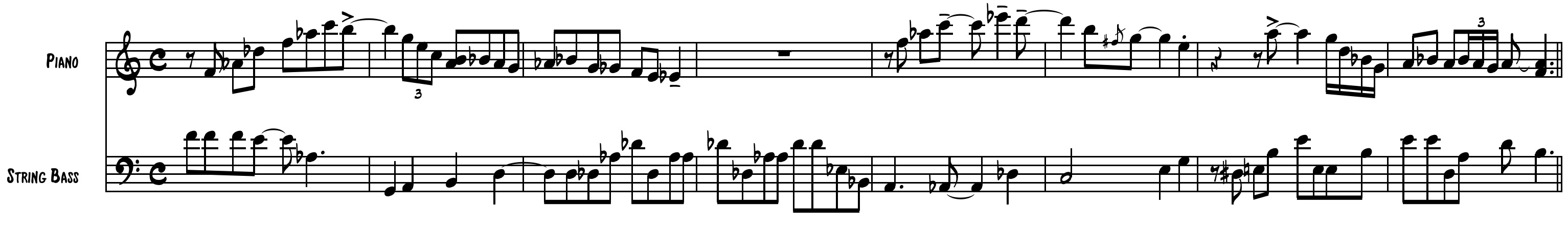

At first listen, Evan’s opening lacks the characteristic pick-up notes that lead into the original song form. In fact, he omits the original song melody in all three of his takes, with exception of a slightly paraphrased version on the final chorus of the third take. On closer inspection of all three takes, we discover that in lieu of stating the melody Evans and LaFaro appropriate the suspensions and inversions of the original harmonic structure to delineate their fundamental approach to the song form. They continue to utilize these concepts to inform improvisation and interaction during the solo choruses as well. By comparing the heads and solo choruses of all three takes, the following harmonic sketch can be rendered, with some variations noted below the staff (Fig. 3).

- Fig. 3: “All of You” – The Bill Evans Trio – Composite rendering (Takes 1-3)

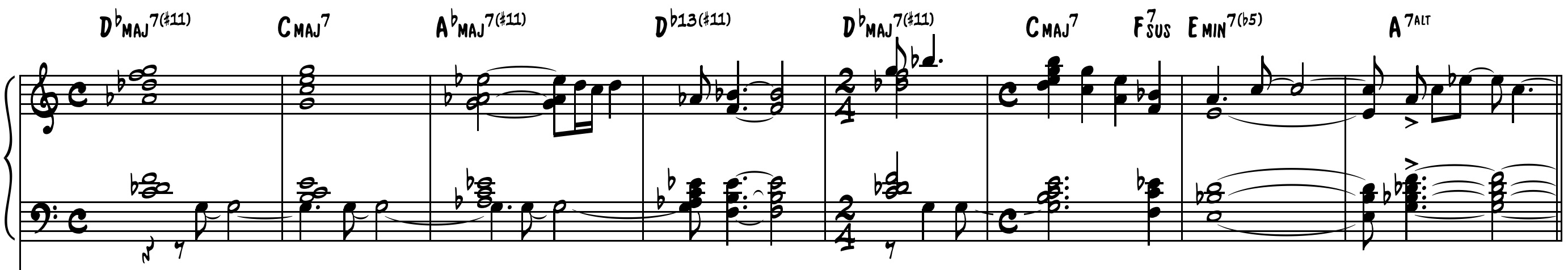

Evans performs the chord extensions and alterations as notated above with little variance, especially during the head. He specifically includes the root in his right hand voicing to supply dissonance to both the major 7th and the pedal tone, as notated in the transcription of the first eight measures of the first take (Fig. 4).

/Click on bars to listen :/ Bill Evans - The Complete Village Vanguard Recordings, 1961

All Of You (Take 1)

All Of You (Take 2)

All Of You (Take 3)

- Fig. 4: “All of You” (Take 1) – 0:00

Interaction and Elastic Leadership

On the surface, the trio’s harmonic structure appears to remain largely intact in all three recorded takes, but intermusical analysis reveals that none of the individual parts could have come into being without interacting with others. In each version, Evans begins the piece alone with a prominent G3-pedal tone at the bottom of his left hand. LaFaro continues the feeling of ongoing suspensions with a series of other pedal tones upon his entrance in m9 and they finally reach the tonic in the second measure of the second A section, directly correlating to the original song form. On the first and second takes, an Ab pedal point on LaFaro’s bass is very prominent throughout the second half of the head, offering a completely different level of dissonance. Whereas the G pedal against the Dbmaj9(#11) and Db13(#11) produces a double dissonance (G-Db tri-tone and G-Ab m9), the Ab pedal results in a lesser but still pungent major 7th dissonance against the #11 (Fig. 5).

- Fig. 5: “All of You” (Take 1) – 0:22

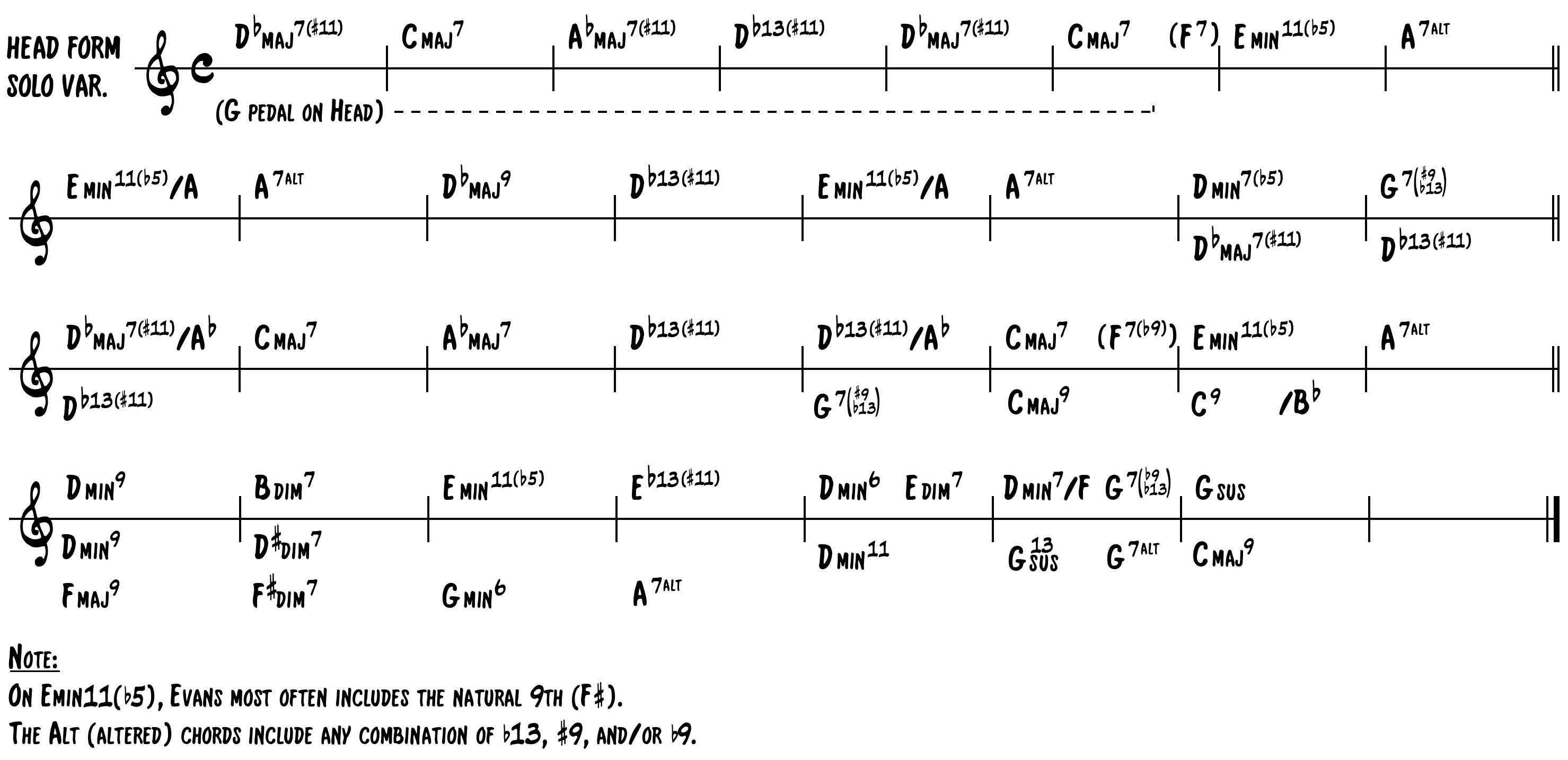

Of the variations notated in Fig. 3, Evans and LaFaro exercise their individual freedoms during the course of performance to choose such elements as a Dbmaj9(#11) or a Db13(#11) – cued entirely by the presence of a C natural or C flat. In the case of the latter chord, the duality of a tri-tone substitution renders the Db13(#11) into G7(b13, #9) simply by LaFaro’s placement of G in the bass instead of Db. Similarly, there are instances in which LaFaro consolidates the Emin9(b5) – A7alt into a singular dominant suspension-resolution by placing the A at the root of the Emin9(b5). It is within this elasticity of leadership roles that allows the bass to direct the harmonic movement in the first four measures of the C-section. On the head, the progression sounds as Dmin13-Bdim7-Emin11(b5)-Eb13(#11)-Dmin6 (Fig. 6).

- Fig. 6: “All of You” (Take 1) – 0:32

But in other instances, the bass dictates several other outcomes as well. For example, in the same place of the form during the first solo chorus, the bass influences both the pitches and pacing of the harmonic sequence. In this particular case, his F-F#-G in the second and third measures delays the Emin7(b5) until the fourth measure, thus softening the return to Dmin in the fifth. Though Evans voices F7-C7 in the second and third measures, LaFaro’s passing line underneath elicits a sense of F7-F#dim7-Gmin13 (Fig. 7).

- Fig. 7: “All of You” (Take 1) – 1:13

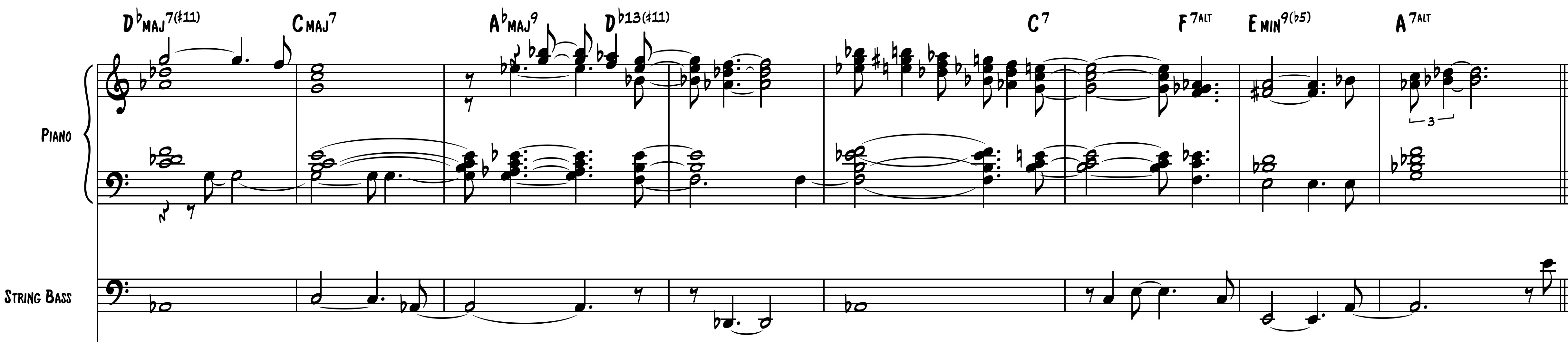

Observing the C-section of the head across all three takes and all three instrumentalists is even more revealing. In each take, Evans supplies his bandmates with a different rhythmic sequence. Though they vary from take to take, the repetitiveness of these divergent patterns invites anticipated responses from LaFaro and Motian. By utilizing varying degrees of direct emulation, fills, and overt departures, the decisions of the bassist and drummer produce three markedly difference leads into the first solo chorus (Fig. 8-10).

- Fig. 8: “All of You” (Take 1) – 0:32

- Fig. 9: “All of You” (Take 2) – 0:33

- Fig. 10: “All of You” (Take 3) – 0:38

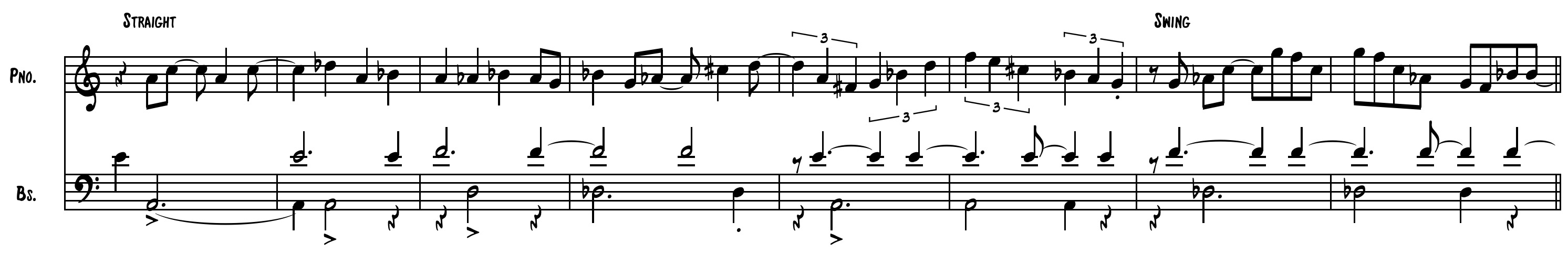

Rather than analyzing the vertical stacks of harmonies and the variations of chord voicings and alterations produced when Evans and LaFaro overlap, improvised decisions made by each musician when interacting with one another produces a range of rhythmic and textural variances that distinguish each recorded take. For instance, the first and third takes begin with the same three-measure polyrhythm created by a sequence of dotted quarter notes (Figs. 8 and 10). In Take 1, bassist LaFaro matches Evans’ rhythm with a D pedal point before departing with a soloistic arpeggio of off-beat quarter notes (Fig. 8). During the same take, drummer Motian punctuates the first, sixth, seventh, and eighth occurrences of the sequence with a cymbal, but allows his comping snare drum to fill the space in direct contrast. On Take 3 however, neither LaFaro nor Motian join Evans’ polyrhythmic sequence, opting instead for whole notes in the bass line and cymbal hits (Fig. 10). Take 2 is the most divergent of the three takes. Evans, LaFaro, and Motian function mostly independently of one another and the groove, resulting in a “floating” sensation of time. Evans’ quarter notes with accents on beats two and four foreshadows a return to time, but LaFaro and Motian refrain from overt declarations of the pulse until they set up the next chorus in the final beat and a half (Fig. 9). In fact, the interaction between musicians during these final two measures produces marked entrances into the first solo chorus on each take. During the first two takes, Evans’ straight eighth notes on the upbeats contrasts with the swing groove that both precedes and succeeds it (Figs. 8-9). Motian supports this momentary shift in groove by offering (unswinging) sixteenth notes on accented downbeats in the first take and by laying out altogether in the second. For the third take however, he extends his influence on the outcome with a measure of triplets that produces such a strong notion of the swing feel that LaFaro and Evans seemingly have little choice but to remain swinging through the final two measures of the C section into the first solo chorus (Fig. 10).

With exception of this initial harmonic statement of the melody-absent head, the remaining form is often not as easily derived, particularly because of the interweaving, contrapunctual lines that seem to flow in complete disregard to the formal structure of the song form. Variations of chord inversions, modalities, polytonalities, pedal points, piano voicings, bass double stops, and any combination thereof, occur both within and outside the expected tonal and rhythmic structures. When the three equal voices of the trio occur simultaneously in accordance with and/or in conflict of the macro and micro-harmonic and rhythmic schemata of the song form, we as listeners (and analysts) become less concerned with the intricate polyphony of notes and rhythms than the constant interaction between several gestural layers.

Gestural Interplay and Rhythmic (Dis)placement

Musically-speaking, the anticipation, delay, and/or accentuation of phrases, ideas, or musical gestures not only produce polyrhythmic notions of time, but also polychordal and alternate tonalities. These are all present in the Evans/LaFaro/Motian recordings, and their significance in the trio’s overall conception is revealed in Marian McPartland’s conversation with Bill Evans for a 1979 broadcast of Piano Jazz. Evans explains:

As far as the jazz thing goes, I think the rhythmic construction of the thing has evolved quite a bit. Now I don’t know how obvious that would be to the listener, but the displacement of phrases and […] the way phrases follow one another in their placement against the meter and so forth is something that I’ve worked on rather hard. And it’s something I believe in. It has little to do with trends… it has more to do with my feeling about my basic conception of jazz structure and jazz melodies and the way the rhythmic things follow one another. And so I just keep trying to get deeper into that and as the years go by, I seem to make some progress in that direction and do some things which please myself and I know it’s happening [24].

McPartland asks Evans to demonstrate rhythmic displacement for her on “All of You”. Those familiar with McPartland’s show know that she likes to play alongside her guests in impromptu duets. However, Evans displaced his phrase structure so much that the host struggled to join in altogether, though the former insisted that he had exaggerated the technique to best illustrate its implementation. Evans’ phrases accentuate metric subdivisions of the beat with apparent disregard for the standard eight-bar phrase structure.

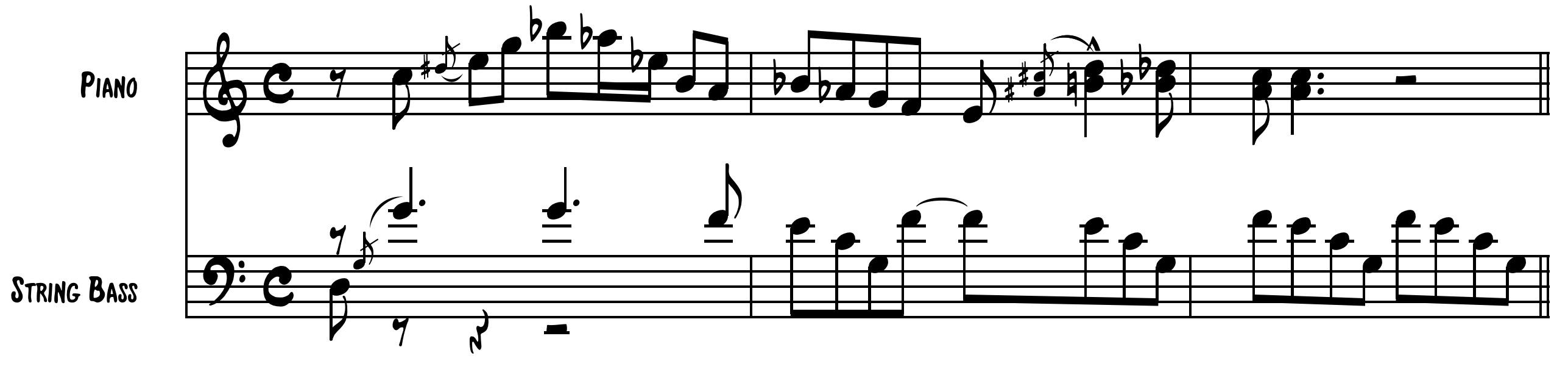

When layered in a triad of equal voices as in Evans’ trio, overlapping tonalities, rhythms, and melodies simultaneously collide and fuse together. Each player in this particular trio freely exercises his right to interpret the song structure and his instrument’s role within a more generalized framework, thus negating the idiomatically-presumed eight-measure divisions of a 32-bar song form and supplanting it with several gestural layers. From the onset of the first solo chorus, Motian’s unpredictable comping and LaFaro’s combination of registral shifts, pedal tones, and double stops instantly elicits an ambiguity of form. When Evans introduces a seemingly “out of time” G melodic minor scalar motive in the seventh measure of his first solo chorus, the ear focuses exclusively on the unraveling of this melodic gesture rather than the prescribed harmonic progression until its completion with the C major tonic chord nearly a dozen measures later. Evans’ addition of the Db during the eighth measure strengthens the F# leading tone with an F# diminished scale (Fig. 11).

- Fig. 11: “All of You” (Take 1) – 0:50

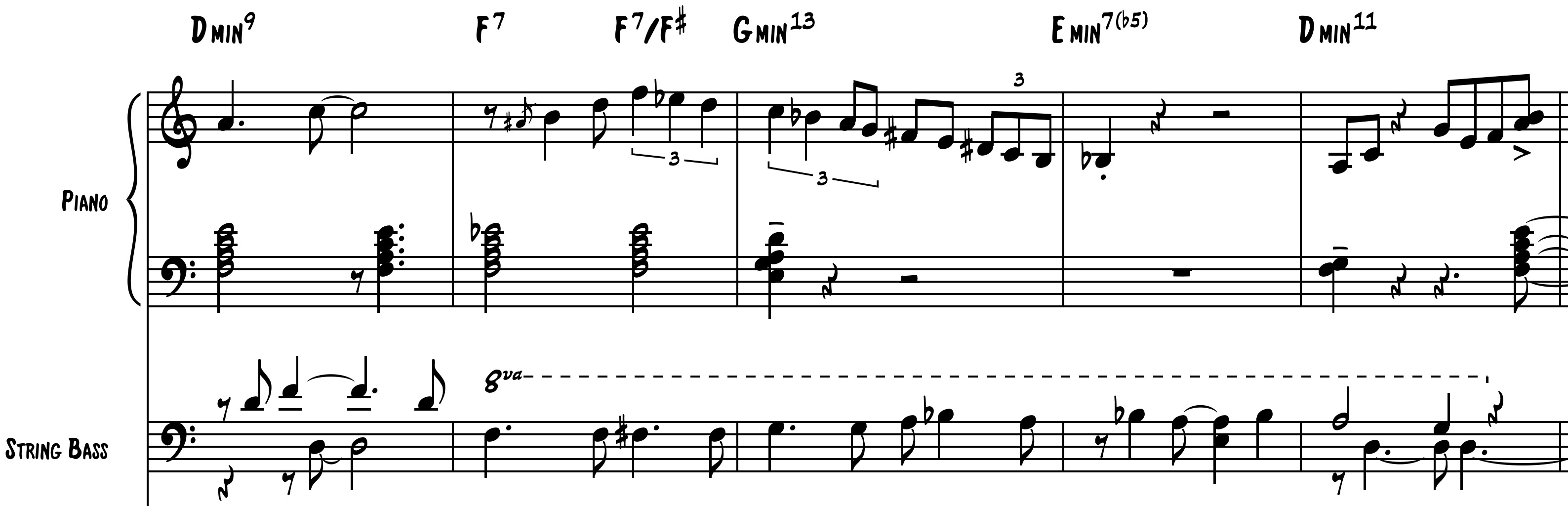

On this first take, two aspects of Motian’s playing allow the drums to be distinctly present without masking the intricacy of the piano and bass interactions: the exclusive use of brushes throughout and the seemingly limitless sustain of the “sizzle” ride cymbal both add to the overall effect. The interplay between Evans and LaFaro is so active during the second chorus that as the two trade ideas with continuous overlap, they almost seem to be diametrically opposed to each other. The reduced score in Figures 12-14 isolates Evan’s right hand and LaFaro’s bass in an effort to elucidate the relations between the two. At times, one will momentarily simplify what he is playing or lay out altogether to make room for the other; in other instances, the juxtaposition of two parts adds rhythmic and tonal dissonance. As Evans concludes the first chorus with an authentic cadence (in this case, G7alt-Cmaj13), LaFaro introduces a 4-note riff of eight notes in the upper register that sets up an entire chorus of piano-bass dialogue (Fig. 12).

- Fig. 12: “All of You” (Take 1) – 1:19

Evans pauses a moment before reentering, at which point LaFaro briefly retreats to a walking bass line. He only stays there for a moment before asserting another 4-note riff of eight notes beneath Evans, who once again steps aside for his bassist. The two jockey positions once more before ending the first A-section with no apparent harmonic agreement (Fig. 13).

- Fig. 13: “All of You” (Take 1) – 1:22

The discord is temporary, however, as the two reach an agreement in the ensuing B-section, when Evan’s straight eight notes, quarter notes, and quarter note triplets over LaFaro’s sustained, large-interval double stops mutually suspend the time feel. In the final two bars of the B-section, Evans dictates a return to swing and a continuation of the dialogue that opened the second chorus (Fig. 14).

- Fig. 14: “All of You” (Take 1) – 1:32

Conclusion

In considering the intermusical implications of the Bill Evans Trio in live performance, the analysis codifies the fact that the distinct interaction and interplay of three equal constituents – Bill Evans, Scott LaFaro, and Paul Motian – is unique to this particular collaboration at this particular moment in space and time and can never be replicated, notwithstanding the fact that this recording session would be this trio’s last. As such, it is vital in improvised performance to consider the influence of all participants in shaping the conceptualization, artistic direction, and final product. It is not merely enough to claim knowledge of a musician’s thought process based on a solo transcription alone. In fact, even fifteen years later at the release of his album Spring Leaves (Milestones 1976), Evans fondly reflects upon the uniqueness of this particular relationship:

Scott was just an incredible guy about knowing where your next thought was going to be. I wondered, ‘How did he know I was going there?’ And he was probably feeling the same way. The most marvelous thing is that he and Paul and I somehow agreed without speaking about the type of freedom and responsibility we wanted to bring to bear upon the music, to get the development we wanted without putting repressive restrictions upon ourselves [25].

Ten days after the Vanguard date, LaFaro was killed when his car veered off a dark rural road and into a tree while driving back late at night from his parents’ home in upstate New York. In the years that followed LaFaro’s death, Evans’ ongoing struggle to find an adequate bassist for his trio not only points to the special musical connections shared between these musicians, but more poignantly the personal. While it is true that intermusical analysis brings to life the interactions that produce a distinctive musical outcome, it directs us to what formulates the most meaningful expressions:

What is most important is not the style itself but how the style is developed and how you can play within it […] What gave that trio its character was a common aim and a feeling of potential. The music developed as we performed, and what you heard came through actual performance. The objective was to achieve the result in a responsible way. Naturally, as the lead voice, I might have shaped the performance, but I had no wish to be a dictator. If the music itself did no coax a response, I did not want one. Meeting both Scott and Paul was probably the most influential factor in my career. I am thankful that we recorded that day, because it was the last time I saw Scott and the last time we would play together. When you have evolved a concept of playing which depends on the specific personalities of outstanding players, how do you start again when they are gone [26]?

Notes

[1] Monson, 1996, p. 81.

[2] Rinzler, 1988, p. 154.

[3] Ibid., p. 155-158.

[4] Berliner, 1994.

[5] Ibid., p. 353.

[6] Ibid., p. 349.

[7] Ibid., p. 348.

[8] Ibid., p. 362.

[9] Monson, 1996.

[10] Ibid., p. 7.

[11] Ibid., p. 3.

[12] Ibid., p. 5.

[13] Berliner, 1994, p. 353.

[14] Monson, 1996, p. 29.

[15] Ibid., p. 74.

[16] Ibid., p. 97-106.

[17] Ibid., p. 125-126.

[18] Ibid., p. 128.

[19] In Williams, 1984.

[20] In Pettinger, 1998, p. 94.

[21] In LaFaro-Fernández, et al., 2009, p. 102.

[22] In Pettinger, 1998, p. 111, originally quoted in Hennessey, 1985, p. 8-11.

[23] In Pettinger, 1998, p. 102.

[24] In McPartland, 2002.

[25] In Pettinger, 1998, p. 114, originally quoted in Conrad Silvert, Spring Leaves liner notes (Milestones M-47034, 1976).

[26] Ibid., originally quoted in Hennessey, 1985, p. 8-11.

Author(s)

Michael Mackey is entering his final stages as a Ph.D. Candidate (ABD) at the University of Pittsburgh, where he served as a teaching fellow and instructor for five years. His dissertation focuses on the piano trio conceptualizations of Pittsburgh-born jazz pianist Ahmad Jamal and his trio’s influence on the format in the 1950s, with particular note on the admiration and musical emulation by legendary trumpeter and bandleader Miles Davis in the formation of his first great quintet. Mackey also works as an accompanist at the Conservatory of the Performing Arts at Point Park University, music director at Holy Child Church, and freelance musician in the Pittsburgh area.

Bibliography

Berliner, Paul, Thinking in Jazz: The Infinite Art of Improvisation, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1994.

Hennessey, Brian, “Bill Evans: A Person I Knew” in Jazz Journal International, March 1985.

LaFaro-Fernández, Helene and Chuck Ralston, Jeff Campbell, and Phil Palombi, Jade Visions: The Life and Music of Scott LaFaro, Denton, University of North Texas Press, 2009.

Monson, Ingrid, Saying Something: Jazz Improvisation and Interaction, Chicago, The University of Chicago Press, 1996.

Pettinger, Peter, Bill Evans: How My Heart Sings. New Haven, Yale University Press, 1998.

Rinzler, Paul, “Preliminary Thoughts on Analyzing Interaction Among Jazz Performers” in Annual Review of Jazz Studies, 1988.

Wilner, Donald L., Interactive Jazz Improvisation in the Bill Evans Trio (1959-61): A Stylistic Study for Advanced Double Bass Performance, Dissertation, University of Miami, 1995.

Williams, Martin, “Hommage to Bill Evans”, in accompanying booklet to The Complete Riverside Recordings. Riverside R-018, 1984.

Discography

Evans, Bill, Bill Evans: The Complete Village Vanguard Recordings, 1961, New York, Riverside 3RCD-4443-2, 2005. Originally Recorded June 25, 1961 and released on two LPs: Sunday at the Village Vanguard (Riverside 1961) and Waltz for Debby (Riverside 1961).

McPartland, Marian, Marian McPartland’s Piano Jazz with Guest Bill Evans, The Jazz Alliance TJA-12038-2, 2002. Originally recorded November 6, 1978.

Michael P. Mackey : « Improvisation, Interaction and Intermusicality in the Bill Evans Trio » , in Epistrophy - Jouer Jazz / Play Jazz.02, 2017 - ISSN : 2431-1235 - URL : https://www.epistrophy.fr/improvisation-interaction-and.html // On line since 22 January 2017 - Connection on 24 April 2024.